Action and reaction; Newton’s 3rd law tells us that for every action there is an equal an opposite reaction. Nature, in effect, is a banker whose accounts are carefully balanced according to the principle of double-entry bookkeeping. Modern theories emphasize this point of view by saying that at the fundamental level all interactions are mediated by the exchange of ‘force quanta’ that transfer energy, momentum, and angular momentum. So all is well – or is it?

Often textbooks muddy the water of this ‘simple’ situation by engaging in nuanced discussions and citing exceptions without emphasizing two points. One is that action-reaction is always honored. The second is that it may require careful logic supported by exact experiements to rescue new cases that seem to be the exception.

Now, these nuances and exceptions, which roughly fall into three prototypical classes, are real and need to be addressed. Each is interesting in its own right, helping to illustarte and explore the richness of the action-reaction concept, but the ‘answer’ for each of these cases is always the same – there are degrees of freedom that are being ignored that balance the action-reaction.

Case 1 – Dissipative forces

Friction is one of the earliest examples of what is discussed in which action-reaction seems to be violated. Energy is bled out of the system and the motion eventually comes to a halt. The prototype example is the damped harmonic oscillator. Its equation of motion is given by

\[ m {\ddot x} + \Gamma {\dot x} + k x = 0 \; , \]

with the general solution

\[ x(t) = A e^{-\gamma t} \cos( \omega t + \phi ) \; , \]

with $$\gamma = \Gamma/2m$$ and $$\omega = \sqrt{\Gamma^2/4 m^2 – k/m}$$.

It is natural to ask, where does the energy go? In this model, the energy disappears with no account as to where and how. Of course, the accepted answer is straightfoward enough. The energy goes into heat; into degrees of freedom not directly tracked by this model. There is balance on the action-reaction front. There is a reaction force of the oscillator on the environment and it is this force which transfers the energy to the surroundings.

While this accepted answer is known to virtually everybody who’s taken a physics class, it is worth pausing to consider that it wasn’t neccessarily obvious to those who first grappled with this problem, nor is it obvious to the beginner who is introduced to it. In fact, it is very difficult to find a detailed argument that traces through all of the evidence in a logical fashion. It is simply common knowledge supported by our belief in the balance of action and reaction.

Case 2 – Driving forces

The second case, which is actually closely related to the first, involves a driving force that maintains some aspect of the system. Energy, momentum, and/or angular momentum enter and leave the system without being explicitly tracked. The best example of such a system is the circular restricted three-body problem. There are numerous applications of this model to spaceflight, with many missions exploiting the $$L_1$$ and $$L_2$$ Lagrange points.

In the circular-restricted three-body problem, two massive bodies are in orbit around their common barycenter. This motion honors action-reaction perfectly with the gravitational force between the bodies being equal and opposite. The ‘forced motion’ which breaks action-reaction, takes place in the idealization where a test particle is introduced into the system. The test particle is thought to be so small that its back-reaction on the motion of the two bodies can be ignored. The equation of motion is

\[ \ddot {\vec r} = m_1 \frac{\vec r_1 – \vec r}{|\vec r_1 – \vec r|^3} + m_2 \frac{\vec r_2 – \vec r}{|\vec r_2 – \vec r|^3} \; ,\]

with the motion of the primaries given by

\[ \vec r_1 = m_2 L \left( \cos(\omega t) \hat \imath + \sin(\omega t) \hat \jmath \right) \]

and

\[ \vec r_2 = -m_1 L \left( \cos(\omega t) \hat \imath + \sin(\omega t) \hat \jmath ) \right) \]

and with

\[ \omega = \frac{G(m_1 + m_2)}{L^3} \; . \]

That the motions of $$m_1$$ and $$m_2$$ are set by their interaction with no influence from the test particle is the source of the driving force. So, by construction, the model violates Newton’s third law.

But often treatments of the circular-restricted three-body problem confuse this simple point by dwelling on the conservation of the Jacobi constant. This conservation is clearly an important point as it helps in the understanding of the global properties of the solutions. Nonetheless, discussions about its importance rarely emphasize that while the model violates action-reaction, real physical situations do not. The conservation of the Jacobi constant is a useful tool but it does not actually occur in nature. Rather a close approximation results. While this distinction may seem subtle in theory it is quite important in practice – real physical situations cannot be expected to exactly conserve the Jacobi constant.

Case 3 – Velocity-Dependent Forces

The case of velocity-dependent forces is perhaps the most confusing member of this list. There are two reasons for this. The first is that the physics literature usually employs this term to mean only one kind of velocity-dependent force: the force of magnetism. Second, the force of magnetism cannot be studied without direct analysis of the fields that act as intermediaries. This latter point should be one of clarity in the community when in fact it is often one of confusion.

Case in point, the discussion in Chapter 1 of Goldstein’s Classical Mechanics concerning the weak and strong forms of action-reaction pairs. Goldstein has this interesting point to make about action and reaction

He goes on to say that:

Of course, this is eactly the well-known conservation law discussed in a previous post on Maxwell’s equations. There is no reason to erode the confidence in the reader by the inclusion of quotes around the field angular momentum.

The situation is somewhat relieved by a footnote that attempts to give concrete scenarios. There are two of them and this post will deal with them in turn.

The first part states

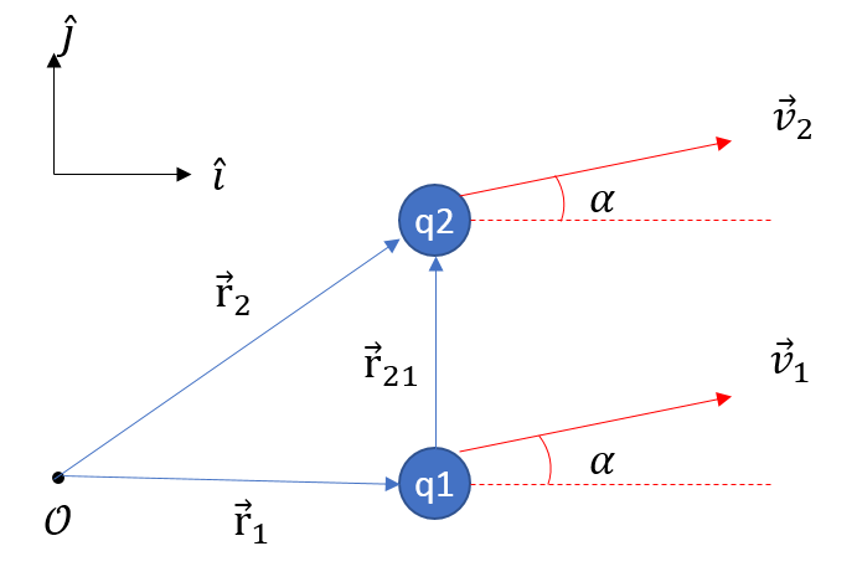

which, diagrammitically, looks like

Since there are only two particles, the most economical description has their motion take place in a plane. The parallel velocity vector is

\[ \hat v = \cos(\alpha) \hat \imath + \sin(\alpha) \hat \jmath \]

and the separation vector between them is

\[ \vec r_{12} = \vec r_{1} – \vec r_{2} = \rho \hat \jmath \; .\]

The combined electrostatic and magentic force on particle 1 due to particle 2 is

\[ \vec F_{12} = \frac{q^2}{4 \pi \rho^2} \left[ \mu_0 \hat v \times ( \hat v \times \hat y ) – \frac{1}{\epsilon_0} \hat y \right] \; .\]

Substituting in the form of $$\hat v$$ and simplifing gives

\[ \vec F_{12} = \frac{q^2}{4 \pi \rho^2} \left[ \mu_0 \left( \sin(\alpha) \cos(\alpha) \hat \imath – \sin^2(\alpha) \hat \jmath \right) – \frac{1}{\epsilon_0} \hat y \right] \ ;. \]

Since the only thing that changes in computing the force on particle 2 due to particle 1 is the sign on the relative position vector it is easy to see that

\[ \vec F_{21} = -\vec F_{12} \]

and action-reaction is honored. However, this force is action-reaction in its weak form where the forces don’t lie along the vector joining the two particles. This conclusion is best supported by computing the $$x$$-component of the force

\[ \vec F_{12} \cdot \hat \imath = \frac{q^2}{4 \pi \rho^2} \mu_0 \sin(\alpha) \cos(\alpha) \; , \]

which is zero for only a few isolated angles.

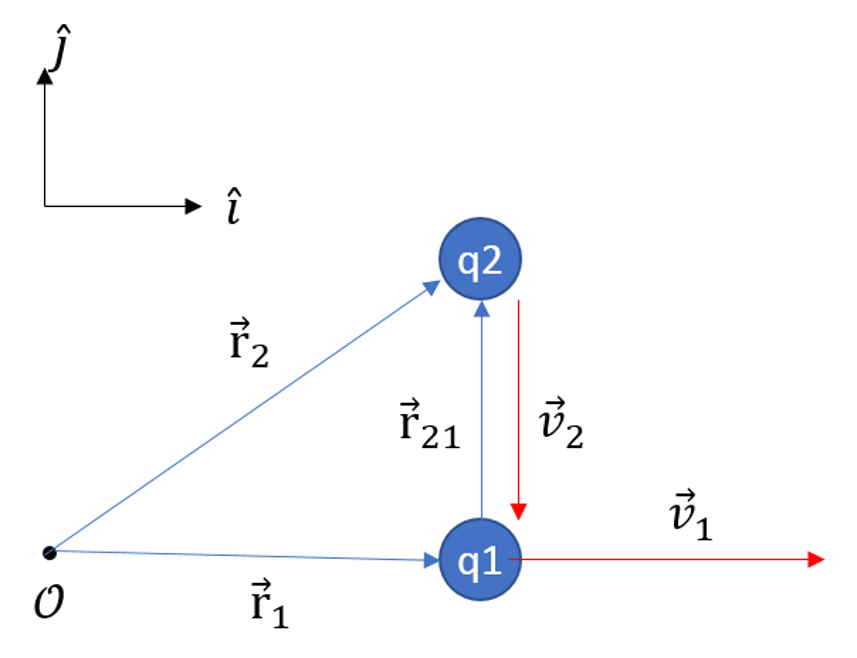

The second part of the footnote states

The scenario here can be pictured as

Now the statement in this footnote is clearly gibberish and it is corrected in the 3rd edition to change ‘nonvanishing force’ to ‘nonvanishing magnetic force’, so we’ll focus solely on magentic force.

From the Biot-Savart law the magnetic force on particle 1 due to particle 2 is

\[ \vec F_{12} = -\frac{\mu_0 q^2 v^2}{4 \pi \rho^2} \hat \imath \times ( \hat \jmath \times \hat \jmath ) = 0 \]

while the force on 2 due to 1 is

\[ \vec F_{21} = \frac{\mu_0 q^2 v^2}{4 \pi \rho^2} \hat \jmath \times ( \hat \imath \times \hat \jmath ) = \frac{\mu_0 q^2 v^2}{4 \pi \rho^2} \hat \imath \neq 0 \; .\]

Clearly action-reaction seems violated but strictly speaking this is not true. What should be emphasized is that there is a ‘third body’ in the mix, the electromagnetic field and that the action-reaction can be restored (although not quite point-wise) by looking for additional degrees of freedom.