The last column presented the general theory of the method of moving frames and the concept of a minimal frame in which the time derivatives of the basis vectors, when expressed in terms of themselves, requires only two parameters rather than the usual 3. Building on that work, this column has a two-fold aim. The first is to apply these techniques to the often-studied space curve of the the twisted cubic. The second aim is to touch base with earlier columns on moving frames, thus relating the nature of the moving frame (whether minimal or not) to the traditional concept of angular velocity and, in the process, shine light on the concept of a minimal frame from a new angle.

The twisted cubic, which is the star in this month’s drama, is defined as a curve in three dimensions given by:

\[ \vec r(t) = t \hat e_x + t^2 \hat e_y + t^3 \hat e_z \; , \]

where the parameter $$t$$ can be regarded as time.

Since they will be needed later, the velocity and acceleration of the twisted cubic are given by

\[ \vec v(t) = \hat e_x + 2 t \hat e_y + 3 t^2 \hat e_z \; \]

and

\[ \vec a(t) = 2 \hat e_y + 6 t \hat e_z \; , \]

respectively.

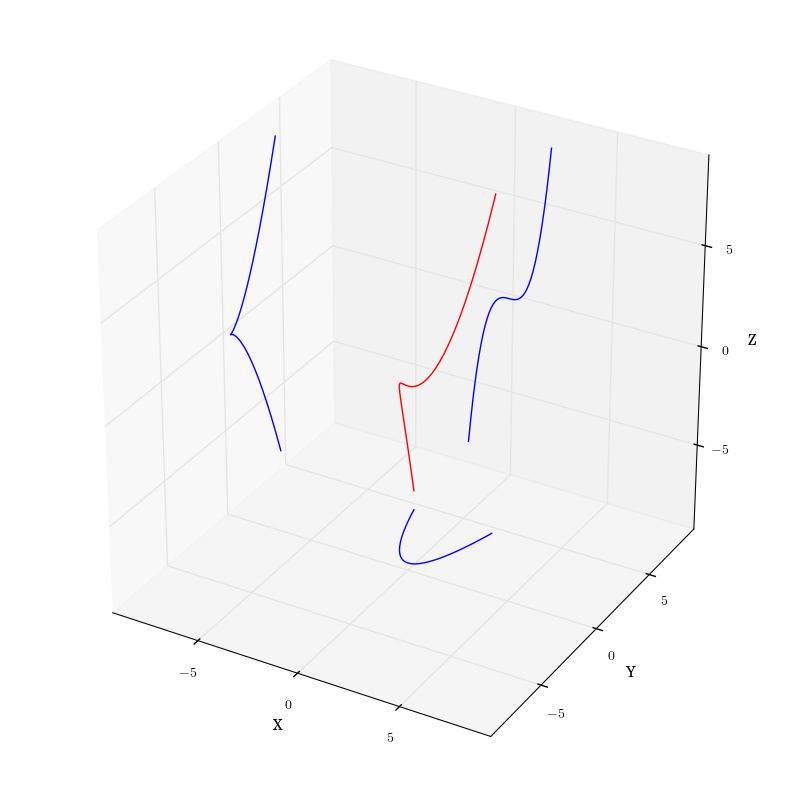

The twisted cubic, shown in the following figure for the range $$t \in [-2,2]$$, has an unusual shape that is best revealed by projecting it to the three coordinate planes. In the $$x-y$$ plane, the curve’s projection is a simple parabola (i.e. $$y(x) = x^2$$). In the $$x-z$$ plane, the curve’s projection is a simple cubic (i.e. $$z(x) = x^3$$). Nothing amazing here. The interest lies in the projection into the $$y-z$$ plane, where a ‘cusp’ appears when $$t$$ passes through the value of 0.

To apply the method of moving frames, the VBN and RIC coordinate frames will be used. VBN is not minimal and RIC is, so there is a nice opportunity to compare and contrast.

While both frames were discussed in the previous column, it is convenient to reiterate their definitions and to present in detail their derivatives. In this later case, some new results will be presented.

The VBN frame is defined as

\[ \hat V = \frac{\vec v}{|\vec v|} \; ,\]

\[ \hat N = \frac{ \vec r \times \vec v }{ | \vec r \times \vec v | } \;, \]

and

\[ \hat B = \hat V \times \hat N \; .\]

Using the general results derived last time, the derivative of $$\hat V$$ is expressed as

\[ \frac{d \hat V}{dt} = \frac{\vec a}{|\vec v|} – \vec v \left( \frac{\vec v \cdot \vec a}{|\vec v|^3} \right) \; .\]

It will be convenient to define $$\vec L = \vec r \times \vec v$$. Doing so allows for the time derivative of $$\hat N$$ to be compactly written as

\[ \frac{d \hat N}{dt} = \frac{\vec r \times \vec a}{|\vec L|} – \vec L \left( \frac{\vec L \cdot \dot{\vec L}}{|\vec L|^3} \right) \; ,\]

where $$\dot{\vec L} = \vec r \times \vec a$$.

The time derivative of $$\hat B$$ is then given in terms of $$\hat V$$ and $$\hat N$$ and their derivatives as

\[ \frac{d \hat B}{d t} = \frac{d \hat V}{d t} \times \vec N + \vec V \times \frac{d \hat N}{d t} \; .\]

The RIC frame is defined by

\[ \hat R = \frac{\vec r}{|\vec r|} \; ,\]

\[ \hat C = \frac{ \vec r \times \vec v }{ | \vec r \times \vec v | } \; ,\]

and

\[ \hat I = \hat C \times \hat R \; .\]

The time derivative of $$\hat R$$ is

\[ \frac{d \hat R}{dt} = \frac{\vec v}{|\vec r|} – \vec r \left( \frac{\vec r \cdot \vec v}{|\vec r|^3} \right) \; .\]

which is a formula analogous to the one for $$\hat V$$.

Since RIC’s $$\hat C$$ is the same as VBN’s $$\hat N$$, its time derivative is identical with a minor change in symbols.

The time derivative of $$\hat I$$ is given by

\[ \frac{d \hat I}{d t} = \frac{d \hat C}{dt} \times \hat R + \hat C \times \frac{d \hat R}{dt} \; .\]

As discussed in Cross Products and Matrices, the moving frame’s motion can be expressed in terms of classical angular momentum, with the mapping $$\alpha \rightarrow -\omega_z$$, $$\beta \rightarrow \omega_y$$, and $$\gamma \rightarrow – \omega_x$$.

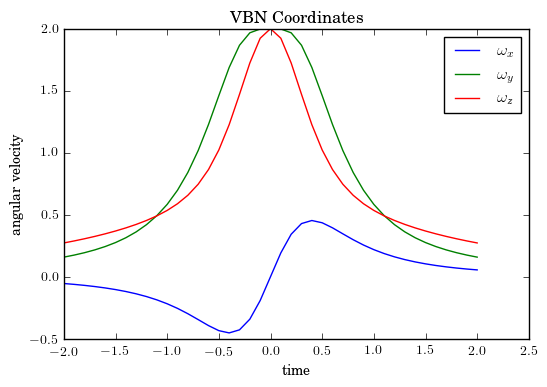

With this mapping in hand, one can see that minimal frames are special in that they only have two non-zero components of their angular velocity. For the twisted cubic, the three components of the VBN angular momentum are

and the three components of the RIC angular velocity are

Note that, in the VBN frame, all three components of the angular velocity are generally non-zero, whereas in the RIC, $$\omega_y$$ is always zero.

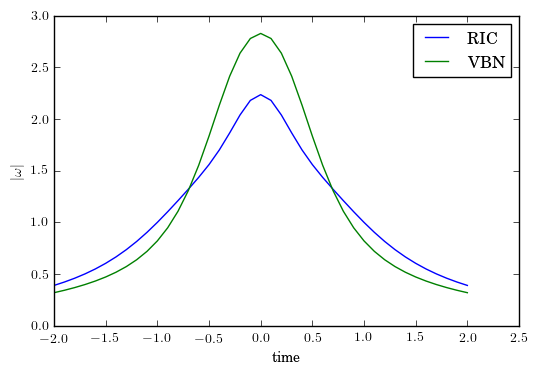

Also interesting is the time evolution of the magnitude of the angular velocity, $$|\mathbf{\omega}|$$, in the two frames.

The VBN frame is generally ‘rotating’ more slowly than the RIC frame away from the ‘origin’ but quickly rises above in the vicinity.

To close, it is important to note that minimal frames are not intrinsically better than non-minimal frames. Minimal frames may be more convenient in some contexts and more inconvenient in others, but it is likely that their best use is in analytic models since the amount of work is reduced by a third.