One of the most confusing aspects of Lagrangian/Hamiltonian mechanics centers on the energy $$E$$ and its relationship to the function $$h$$ (or to the Hamiltonian $$H$$, to which it is closely related). The key questions are, to what extent these two terms can be identified with each other, and which of them is conserved and in which circumstances. The answers have deep implications into the analysis of the possible motions the system supports. The opportunity for confusion arises because there are many different possibilities that show up in practice.

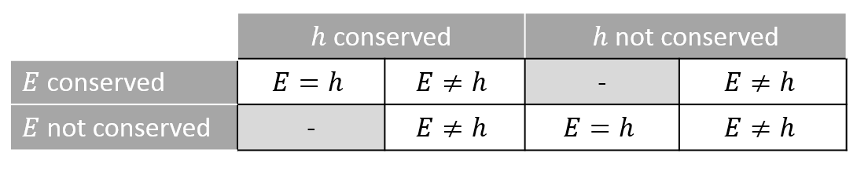

The aim of this and the following columns is to delve into these cases in sufficient detail to flesh out the six logically possible cases that result from $$E$$ being either conserved or not, $$h$$ being either conserved or not, both subject to the possible constraint that $$E=h$$.

Before going into specific analysis of this case or that, it is important to get an overview as to how these various cases result in practice. Central to the variety of possibilities is the notion of generalize coordinates and the application of dynamical constraints.

As discussed in great detail in Classical Mechanics by Goldstein (especially Chapter 1), generalized coordinates are what provide the Lagrangian method with its power by enabling it to rise above Cartesian coordinates and into a frame better adapted to the geometry of the dynamics. For example, central force motion is best described in plane-polar coordinates that not only make the computations easier but also provide a simple method of imposing constraints like, the motion must take place at a fixed radius (e.g., a bead on a loop of wire). The number of generalized coordinates can always match the number of degrees of freedom, a condition that usually can’t be fulfilled in Cartesian coordinates if there are constraints. Generalized coordinates serve as the cornerstone in understanding rigid body motion – the three Euler angles mapping directly to the three degrees of freedom such a body has to move about its center of mass.

The price for such freedom is that the universe of possible conserved quantities must be enlarged from the obvious ones evident in elementary mechanics to a broader set. This expansion in scope leads to the need to distinguish between the energy $$E$$ and the function $$h$$. One of the most important and famous examples of this is the conservation of the Jacobi constant in the circular-restricted three-body problem.

But, before launching into an analysis that compares and contrasts $$E$$ with $$h$$, it is important to establish some basic results of the Lagrangian method.

The first result is that the Lagrangian equations of motion are invariant under what Goldstein calls a point transformation

\[ q^i = q^i(s^j,t) \; , \]

relating one set of generalized coordinates $$q^i$$ to another $$s^j$$ (note that Cartesian coordinates are a subset of generalized coordinates).

Transformation of the Lagrangian $$L(q^i,t)$$ to $$L'(s^j,t)$$ starts with determining the form of the generalized velocities

\[ {\dot q}^i = \frac{\partial q^i}{\partial s^j} {\dot s}^j + \frac{\partial q^i}{\partial t} \; , \]

($$\dot f \equiv \frac{d}{dt} f$$).

From this relation comes the somewhat counterintuitive ‘cancellation-of-the-dots’ that states

\[ \frac{\partial {\dot q}^i}{\partial {\dot s}^j} = \frac{\partial q^i}{\partial s^j} \; .\]

A needed corollary of the cancellation-of-the-dots results from applying the total time derivative to both sides of the above relation. The right-hand side expands as

\[ \frac{d}{dt} \left( \frac{\partial q^i}{\partial s^j} \right) = \frac{\partial^2 q^i}{\partial s^k \partial s^j} {\dot s}^k + \frac{\partial^2 q^i}{\partial t \partial s^j} \; .\]

Switching the order of partial derivatives (always allowed for physical functions) and regrouping terms gives the right-hand side (noting along the way that $$\partial {\dot s}^k / \partial s^j = 0 $$) as

\[ \frac{\partial}{\partial s^j} \left( \frac{\partial q^i}{\partial s^k} {\dot s}^k + \frac{\partial q^i}{\partial t} \right) = \frac{\partial}{\partial s^j} \frac{d q^i}{d t} \; . \]

The next step is to grind through the equations of motion, which is straightforward if a bit tedious. Start by labeling the Lagrangian that results after the substitution of the point transformation as

\[ L’ (s^j,{\dot s}^j,t ) = L (q^i(s^j),{\dot q}^i(s^j,{\dot s}^j),t ) \; .\]

The coordinate-derivative piece of the equations of motion gives

\[ \frac{\partial L’}{\partial s^j} = \frac{\partial L}{\partial q^i} \frac{\partial q^i}{\partial s^j} + \frac{\partial L}{\partial {\dot q}^i} \frac{\partial {\dot q}^i}{\partial s^j} \; . \]

The velocity derivative piece of the equations of motion gives

\[ \frac{\partial L’}{\partial {\dot s}^j} = \frac{\partial L}{\partial {\dot q^i}} \frac{\partial {\dot q}^i}{\partial {\dot s}^j} \; . \]

Combining these pieces into the Euler-Lagrange equations gives

\[ \frac{d}{dt} \left( \frac{\partial L’}{\partial {\dot s}^j } \right) – \frac{\partial L’}{\partial s^j} = \frac{d}{d t} \left( \frac{\partial L}{\partial {\dot q}^i} \right) \frac{\partial {\dot q}^i}{\partial {\dot s}^j} + \frac{\partial L}{\partial {\dot q}^i} \frac{d}{dt} \left( \frac{\partial {\dot q}^i}{\partial {\dot s}^j} \right) \\ – \frac{\partial L}{\partial q^i} \frac{\partial q^i}{\partial s^j} – \frac{\partial L}{\partial {\dot q}^i} \frac{\partial {\dot q}^i}{\partial s^j} \; .\]

Cancellation-of-the-dots and its corollary tells us that the second and fourth terms on the right-hand side cancel, leaving

\[ \frac{d}{dt} \left( \frac{\partial L’}{\partial {\dot s}^j } \right) – \frac{\partial L’}{\partial s^j} = \left[ \frac{d}{d t} \left( \frac{\partial L}{\partial {\dot q}^i} \right) – \frac{\partial L}{\partial q^i} \right] \frac{\partial q^i}{\partial s^j} \; . \]

Since the original equations of motion are zero and the Jacobian of the point transformation is not, we conclude that

\[ \frac{d}{d t} \left( \frac{\partial L}{\partial {\dot q}^i} \right) – \frac{\partial L}{\partial q^i} = 0 \; , \]

which informs us that the Euler-Lagrange equations are invariant under point transformations. This result is our hunting license to use any coordinates related to Cartesian coordinates by a point transformation to describe a system’s degrees of freedom.

The next result is that the Lagrangian is invariant with respect to the addition of a total time derivative. In other words, the same equations of motion result from a Lagrangian $$L$$ as do from one defined as

\[ L’ = L + \frac{d F(q^i,t)}{dt} \; .\]

The proof is as follows. Applying the Euler-Lagrange operator to both sides of the definition of $$L’$$ gives

\[ \frac{d}{dt} \left( \frac{\partial L’}{ \partial {\dot q}^i } \right) – \frac{\partial L’}{\partial q^i} = \frac{d}{dt} \left( \frac{\partial L}{ \partial {\dot q}^i } \right) – \frac{\partial L}{\partial q^i} + \frac{d}{dt} \left( \frac{\partial}{\partial {\dot q}^i} \frac{dF}{dt} \right) – \frac{\partial}{\partial q^i} \frac{dF}{dt} \;. \]

Invariance of the equations of motion requires the last two terms to cancel. The easiest way to see that they do is to first concentrate on the expansion of the total time derivative of $$F$$ as

\[ \frac{d F}{dt} = \frac{\partial F}{\partial q^j} {\dot q}^j + \frac{\partial F}{\partial t} \; . \]

The expression within the third term above then becomes

\[ \frac{\partial}{\partial {\dot q}^j} \left( \frac{d F}{dt} \right) = \frac{\partial F}{\partial q^i} \; . \]

Cancellation of the last two terms now rests on the recognition that

\[ \frac{d}{dt} \left( \frac{\partial F}{\partial q^i} \right) = \frac{\partial}{\partial q^i} \left(\frac{dF}{dt} \right) \; ,\]

a fact easily established by realizing that the total time derivative is a specific sum of partial derivatives and that partial derivatives commute with each other.

This result allows us to play with the form of the Lagrangian in an attempt to find the simplest or most compact way of describing the motion of the physical system.

Next month’s column will use the general structure of this formalism as a guide to the connection between the energy $$E$$ and $$h$$. The columns in the following months will apply the two results derived here to various physical systems in order to illustrate the various cases for $$E$$ and $$h$$ outlined above.