One of the most fascinating problems of classical physics is the circular, restricted, three-body problem (CR3BP). Not only is this problem full of rich behaviors that are not exhibited in the Kepler problem or in the problem of a single body moving in an external unchanging force, but the applications of the CR3BP are numerous. For example, the trajectory that the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) moves along around the Sun-Earth/Moon L2 libration point can only be understood within the context of the CR3BP. Many other spacecraft have been found at these Libration Points, including Wind, ACE, SOHO, WMAP, and the soon-to-be-launched Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope. (Side note: I’ve contributed to all of these missions, often as the flight dynamics lead, and JWST is currently flying the trajectory I designed for it).

In terms of the complexity and hierarchy of dynamics, the CR3BP positions itself at an interesting junction. It is far more complex than the Kepler problem but far simpler than the generic N-body problem making it at least tractable in many areas.

This post will be the first in a series that explores the CR3BP. Here we will establish the equations of motions, explaining along the way, why the word restricted gets attached. We will then show how moving to a rotating frame transforms the problem from being time-dependent (non-autonomous) to time-independent (autonomous). This rotating frame also has the benefit of revealing the existence of a pseudopotential that turns the equations of motion in the rotating frame into a Hamiltonian system (but we will have to wait until a future post to see that). At the end, I’ll comment on what makes the circular case much simpler than the elliptic, restricted, three-body problem.

The argument presented below is highly influenced by Chapter 5 of A E Roy’s book Orbital Motion, 3rd edition.

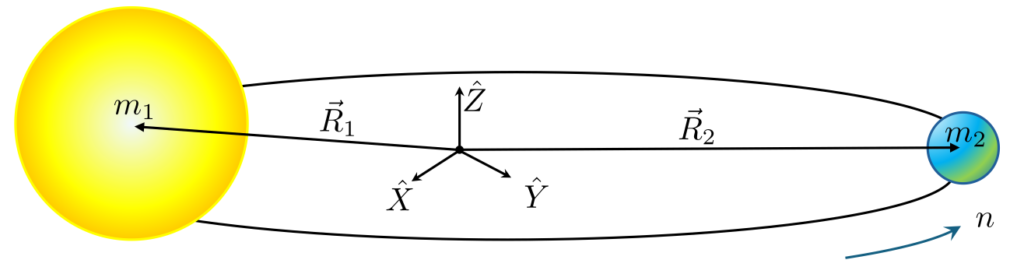

Our study begins with assuming that there are two massive bodies of mass $m_1$ and $m_2$ that are interacting gravitationally with each other. These bodies, referred to as the primary and the secondary, follow motion that is exactly described by the Kepler problem. We layer the additional requirement that the primary and secondary are in circular motion about their center-of-mass with a fixed distance between them of $L$. Under these assumptions, the bodies move at a constant angular rate

\[ n = \sqrt{\frac{G (m_1 + m_2)} {L^3}} \; . \]

Note the use of $n$ (for mean motion) in place of the more traditional elementary symbol $\omega$ for uniform circular motion is to honor the celestial mechanics use. The geometry can be further specified by fixing an inertial coordinate system $\{ {\hat X}, {\hat Y}, {\hat Z} \}$ at the center of mass (with ${\hat X}$ and ${\hat Y}$ in the orbital plane) and by denoting the position vectors of the two bodies with respect to the center of mass as ${\vec R}_1$ and ${\vec R}_2$.

In order to make the treatment universally applicable (e.g., to the Earth-Moon system as well as Sun-Jupiter), units are chosen to make the equations of motion non-dimensional. It is customary in all treatments to pick $L$ as the unit of distance between the masses and the total mass $M = m_1 + m_2$ as the unit of mass. The secondary’s mass is then denoted by the mass fraction parameter $\mu$ (i.e., $m_1 = 1 – \mu$ and $m_2 = \mu$). By its definition $\mu \leq 1/2$. There is no consensus on the choice of the unit of time and there are two reasonable choices: 1) set $G = 1$ so that the angular frequency $n=1$ (i.e., the period of motion is $2 \pi$) or 2) set the unit of time so that the period of motion is unity. We pick option 1) in order to more faithfully follow Roy.

At this point we can introduce the restricted body at a position ${\vec R} = X {\hat X} + Y {\hat Y} + Z {\hat Z}$ and form the equations of motion in the inertial coordinate system (note the mass of the restricted body $m$ plays no role if the forces are solely gravitational)

\[ {\ddot {\vec R}} = – \frac{(1-\mu) ({\vec R}-{\vec R}_1)}{| {\vec R}-{\vec R}_1|^3} – \frac{\mu ({\vec R}-{\vec R}_2)}{| {\vec R}-{\vec R}_2 |^3} \; .\]

While the above equation looks innocent enough, it is worth noting that the force is time-dependent since the primary and secondary execute their motion ignorant of the existence of the restricted body. This point can be driven home if we assume that the line joining the primary to the secondary is aligned with ${\hat X}$ at $t=0$ with the vector pointing to the secondary having a positive value. Their position vectors can be written explicitly as

\[ {\vec R}_1 = -(1-\mu) \left[ \cos t {\hat X} + \sin t {\hat Y} \right] \; \]

and

\[ {\vec R}_2 = \mu \left[ \cos t {\hat X} + \sin t {\hat Y} \right] \; . \]

As a check, one can confirm that at all times $m_1 {\vec R}_1 + m_2 {\vec R}_2 = 0$. Substituting in these expressions transforms the equations of motion (now written in component form] to:

\[ {\ddot X} = -(1-\mu)\frac{X+(1-\mu) \cos t}{D_1^3} + \mu \frac{X-\mu \cos t}{D_2^3} \; , \]

\[ {\ddot Y} = -(1-\mu)\frac{Y+(1-\mu) \sin t}{D_1^3} + \mu \frac{Y-\mu \sin t}{D_2^3} \; , \]

and

\[ {\ddot Z} = -(1-\mu)\frac{Z}{D_1^3} + \mu \frac{Z}{D_2^3} \; . \]

The distances $D_1$ \& $D_2$ between the primary \& secondary and the restricted body, respectively, are given by:

\[ D_1 = \sqrt{ \left[ X + \mu \cos t \right]^2 + \left[ Y + \mu \sin t\right]^2 + Z^2 } \; \]

and

\[ D_2 = \sqrt{ \left[ X – (1-\mu) \cos t \right]^2 + \left[ Y – (1- \mu) \sin t\right]^2 + Z^2 } \; .\]

This form clearly shows that the underlying equations are explicitly time-dependent. Of course, this makes sense since the motion of the restricted particle does not influence the motion of the primary and secondary. Their orbital motion acts like an external force that drives the system but is not part of the system. This is sometimes referred to as the restricted particle reacting to but not ‘back-reacting’ on the other two.

Despite this non-autonomous character, the CR3BP can be cast into a autonomous form. The key insight is to note that since the massive bodies move in circular motion about their center-of-mass, their angular rate is constant. If we construct a co-rotating frame so that it rotates around ${\hat Z}$ and has it’s x-axis aligned with ${\hat X}$ at $t=0$ then $x_1 = -\mu$ and $x_2 = (1-\mu)$, with $y_1=y_2=z_1=z_2=0$ (with the lower case letters indicating the corresponding components of position measured by an observer moving with this frame). and, so, in a co-rotating frame they will appear fixed. We can relate the position components in the inertial frame with those in this co-rotating frame using

\[ X_i = x_i \cos(t) – y_i \sin(t) \; , \]

\[ Y_i = x_i \sin(t) + y_i \cos(t) \; , \]

and

\[ Z_i = z_i \; . \]

The $i$ index specifies the body in question: restricted $i$ is blank, primary $i=1$, and secondary $i=2$.

We now need to re-express the inertial equations of motion in the co-rotating frame. We’ll tackle the terms appearing on the left-hand sides first and then right-hand sides second.

The time derivatives of the position components on the left-hand sides are a bit involved since the transformation to the co-rotating frame is time dependent. Fortunately, only the in-plane components are involved, with the left-hand sides becoming:

\[ LHS_x = {\ddot x} \cos t – 2 {\dot x} \sin t – x \cos t – {\ddot y} \sin t – 2 {\dot y} \cos t + y \sin t \; \]

and

\[ LHS_y = {\ddot y} \cos t – 2 {\dot y} \sin t – y \cos t + {\ddot x} \sin t – 2 {\dot x} \cos t – x \sin t \; .\]

Note that the terms involving a single time derivative (either ${\dot x}$ or ${\dot y}$) appear with opposite signs in the two left-hand sides. This leads to taking linear combinations of the two to isolate the motion for $x$ and $y$, more cleanly:

\[ LHS_x \cos t + LHS_y \sin t = {\ddot x}-2 {\dot y}-x \; \]

and

\[ -LHS_x \sin t + LHS_y \cos t = {\ddot y} + 2{\dot x} – y \; . \]

When we look at the right-hand sides, we see a similar pattern where the in-plane, co-rotating coordinates $x_i$ and $y_i$ mix together when converting each of the independent inertial coordinates. We can grind through substituting in the transformations above and then combining the right-hand sides in the same way as was done for the left-hand sides above (click here for a Jupyter notebook showing all the steps). However, there is an easier way that involves more insight but far less industry. Recognize that since the right-hand side doesn’t depend on time, it can be evaluated completely in the co-rotating frame. In that frame the position of the restricted body is given by ${\vec R} = x {\hat x} + y {\hat y} + z {\hat z}$ and the specific forces (force/restricted mass) arise as if we hadn’t mixed the equations of motion.

The distances between the massives and the restricted are:

\[ d_1 = \sqrt{ (x+\mu)^2 + y^2 + z^2 } \; \]

and

\[d_2 = \sqrt{ (x-1+\mu)^2 + y^2 + z^2} \; ,\]

where the switch has been made from upper case ‘D’ to lower case ‘d’ simply to emphasize the difference in structural forms.

\[ {\ddot x} – 2 {\dot y} = x – (1-\mu) \frac{x+\mu}{d_1^3} – \mu \frac{x-1+\mu}{d_2^3} \; , \]

\[ {\ddot y} + 2 {\dot x} = y – (1-\mu) \frac{y}{d_1^3} -\mu \frac{y}{d_2^3} \; , \]

and

\[ {\ddot z} = -(1-\mu) \frac{z}{d_1^3} – \mu \frac{z}{d_2^3} \; ,\]

This final form has successfully eliminated the non-autonomous nature of the inertial equations. This simplification was possible precisely because the co-rotating frame moves with a constant angular rate (i.e., there are no $\dot n$ in the transformation of the left-hand sides). This special case also explains why the difficulty in allowing the primary and secondary to move on elliptical paths is so much more pronounced.