Last month we formulated a model of and derived the equations of motion for the circular restricted three-body problem (CR3BP). In the CR3BP, two massive bodies, the primary and secondary (collectively called the massives) move in circular motion about their common center of mass, ignorant of the presence of a third body. Since this third body doesn’t influence or back-react onto the massives, it is called the restricted body and, for all practical purposes, it is massless.

The lack of back reaction means that the forces exerted by the massives on the restricted body result from a `schedule’ and do not arise naturally from the motion of all three. The restricted body is, therefore, driven by a external, time varying force making the inertial equations of motion non-autonomous.

Nonetheless, because of the requirement that the massives are moving in circular orbits, their motion has a fixed angular frequency (a feature unique in Keplerian orbits) and we can move to a co-rotating frame in which the equations of motion are autonomous. The cost of that simplification is that there are now ‘Coriolis’ type forces ($-2{\vec \omega}\times{\vec v}$ in basic classical mechanics) in the problem as identified by the presences of first-order time derivatives. The resulting equations of motion are:

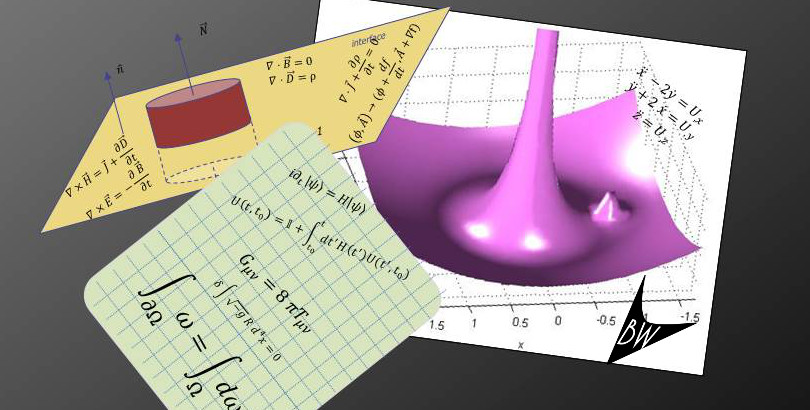

\[ {\ddot x} – 2 {\dot y} – x = – (1-\mu) \frac{x+\mu}{d_1^3} – \mu \frac{x-1+\mu}{d_2^3} \; , \]

\[ {\ddot y} + 2 {\dot x} – y = – (1-\mu) \frac{y}{d_1^3} -\mu \frac{y}{d_2^3} \; , \]

and

\[ {\ddot z} = -(1-\mu) \frac{z}{d_1^3} – \mu \frac{z}{d_2^3} \; ,\]

with $d_1 = \sqrt{ (x+\mu)^2 + y^2 + z^2}$ and $d_2 = \sqrt{ (x – 1 + \mu)^2 + y^2 + z^2 }$.

Note that we’ve rearrange the result from last month so that the right-hand sides contain only the purely gravitational terms and that the terms linear in $x$ and $y$, which are centrifugal ($-{\vec \omega}\times({\vec \omega} \times {\vec r})$ in basic classical mechanics) and also the result of time derivatives in the co-rotating frame, are back on the left.

As discussed last month, despite the mixing of the in-plane inertial coordinates that results when moving to the co-rotating frame, the gravitational terms appear as if we had simply constructed them in the co-rotating frame to begin with. This is not a coincedence but a result of the fact that (unlike velocities) accelerations and forces are vectors that `live’ in the configuration space of the system.

From elementary classical mechanics, we know that gravitational forces are conservative and result from the taking a gradient of an appropriate potential. Therefore, we can expect that a similar potential, of the form

\[ {\tilde U} = -\frac{m_1}{d_1} – \frac{m_2}{d_2} = – \frac{1-\mu}{d_1} – \frac{\mu}{d_2} \; \]

should give rise to the right-hands sides by taking the appropriate derivatives.

We can verfiy this relatively easily by differentiating $U$ (easier that integrating the right-hand sides) and by organizing the derivatives. Defining

\[ d = \sqrt{ (x-x_0)^2 + (y-y_0)^2 + (z-z_0)^2 } \; \]

we can easily verify that

\[ \frac{\partial}{\partial x} d= \frac{x-x_0}{d} \; \]

and

\[ \frac{\partial}{\partial x} \frac{1}{d} = -\frac{1}{d^2} \frac{\partial}{\partial x} d= – \frac{x-x_0}{d^3} \; , \]

with analogous expressions for the derivatives with respect to $y$ and $z$.

Following this program, we see that

\[ \frac{\partial}{\partial x} {\tilde U} = -\frac{(1-\mu)(x+\mu)}{d_1^3} – \frac{\mu(x-1+\mu)}{d_2^3} \; , \]

\[ \frac{\partial}{\partial y} {\tilde U} = -\frac{(1-\mu) y}{d_1^3} – \frac{\mu y}{d_2^3} \; , \]

and

\[ \frac{\partial}{\partial z} {\tilde U} = -\frac{(1-\mu) z}{d_1^3} – \frac{\mu z}{d_2^3} \; . \]

The next step is to recognize is to bring the centrifugal terms back to the right-hand side and to define a related potential

\[ U = \frac{1}{2} ( x^2 + y^2 ) + {\tilde U} = \frac{1}{2} ( x^2 + y^2 ) – \frac{1-\mu}{d_1} – \frac{\mu}{d_2} \;. \]

$U$ is known as the pseudo-potential of Jacobi, who first published its existence in 1836.

The equations of motion now take on the compact form (with $\partial_x U \equiv (\partial/\partial x) U$, etc.) of:

\[ {\ddot x} – 2 {\dot y} = \partial_x U \; , \]

\[ {\ddot y} + 2 {\dot x} = \partial_y U \; , \]

and

\[ {\ddot z} = \partial_z U \; . \]

The existence of the pseudo-potential enables us to make some remarkable predictions on the types of motion that can result from the CR3BP. This is particularly useful given that the these equations have no general, closed form solution.

Start by taking each of the equations above and multiplying by the corresponding first derivative to get

\[ {\dot x}{\ddot x} – 2 {\dot x} {\dot y} = \partial_x U \cdot {\dot x} \; , \]

\[ {\dot y}{\ddot y} + 2 {\dot x} {\dot y} = \partial_y U \cdot {\dot y} \; , \]

and

\[ {\dot z}{\ddot z} = \partial_z U \cdot {\dot z} \; . \]

We can see that by adding these three equations together we can eliminate the Coriolis terms and we are left with

\[ {\dot x}{\ddot x} + {\dot y}{\ddot y} + {\dot z}{\ddot z} = \partial_x U \cdot {\dot x} + \partial_y U \cdot {\dot y} + \partial_z U \cdot {\dot z} \; . \]

Both sides are total time derivatives that can be rewritten as

\[ \frac{1}{2} \frac{d}{dt} \left( {\dot x}^2 + {\dot y}^2 + {\dot z}^2 \right) = \frac{d}{dt} U \; .\]

Collecting the terms on the left-hand side and carrying out the integral gives

\[ \frac{1}{2} \left( {\dot x}^2 + {\dot y}^2 + {\dot z}^2 \right)-U = constant \; . \]

The form of the constant differs somewhat from book to book. We will depart from A. E. Roy here by expressing that constant as $(1/2) C_J$ so that

\[ C_J = 2 U – v^2 \; , \]

where $v^2 = {\dot x}^2 +{\dot y}^2 +{\dot z}^2$. $C_J$ is universally referred to as Jacobi’s constant (even if the form of it isn’t always the same).

Next month, we’ll see how the presence of this constant enables us to understand the limits on the permitted motion without having to solve the equations of motion directly. This global assessment is made possible by examining the geometry of the defining equation for $C_J$ above.